The Age Spectrum of Schizophrenia: Early to Late Onset

Summary

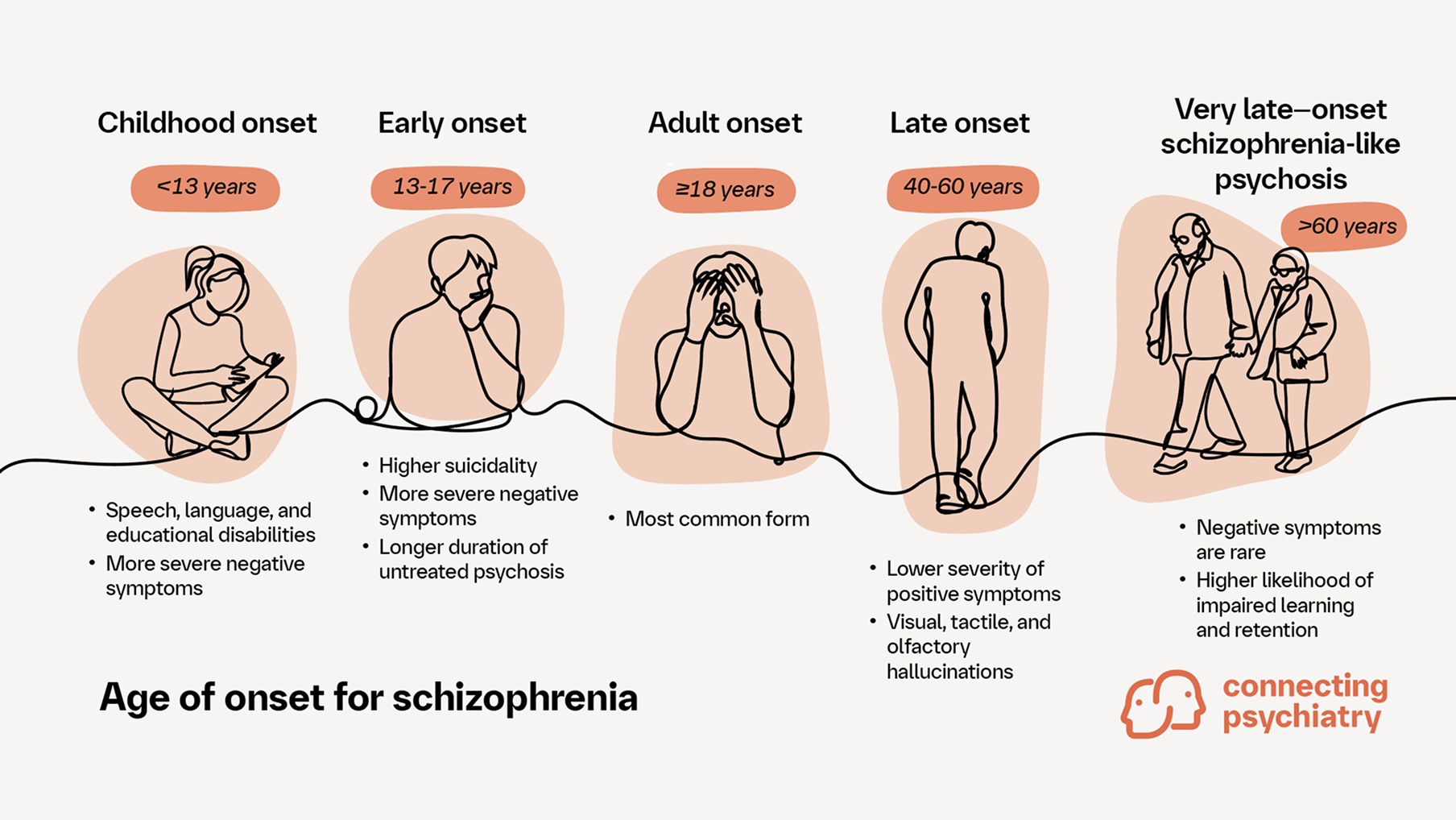

- The onset of schizophrenia typically occurs from the late teens to the early 30s but can also occur in childhood, early adolescence, late adulthood, and very late adulthood

- Patients with childhood- and early-onset schizophrenia are often misdiagnosed due to symptom overlap with other childhood disorders

- Patients with late- and very late–onset schizophrenia-like psychosis may present milder positive symptoms compared with early-onset schizophrenia

- Improved awareness and diagnostic tools are essential for timely and effective diagnosis and intervention

Schizophrenia affects approximately 24 million people worldwide,1 with an incidence rate of approximately 0.45% in adults and approximately 0.05% in children globally.1–4 Onset typically occurs from the late teens to the early 30s, occurring earlier in men (late teens to early 20s) compared with women (20s to early 30s).5 While early adulthood onset was once considered to be a central characteristic of the condition, onset times can vary widely, revealing a complex picture of demographic differences and heterogenous presentation at different ages of onset.6,7

The onset of schizophrenia can be categorized by age as follows: childhood onset before 13, early onset between 13-17, adult onset at 18 and older, late onset between 40 and 60, and very late–onset schizophrenia-like psychosis at 60 and older.8–10 In this article, we explore the varying ages of onset of schizophrenia and characterize the differences between these patient populations.

Early onset, lifelong impact: The challenges of diagnosing childhood- and early-onset schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is a devastating condition, especially when it presents in childhood or adolescence.2 Childhood onset is remarkably rare but represents a more severe form of schizophrenia with more prominent pre-psychotic developmental disorders, brain abnormalities, and genetic risk factors.2,8 Both childhood- and early-onset schizophrenia are often misdiagnosed and have worse outcomes compared with adult-onset schizophrenia, including more negative symptoms, increased premorbid deficits, higher levels of enuresis, higher levels of autistic traits, and a higher risk of treatment resistance.4,11 Cognitive deficits in the same cognitive domains as those in adult-onset schizophrenia have been observed in both childhood- and early-onset schizophrenia, and there is evidence of more severe deficits in executive functions, processing speed, working memory, and verbal memory in comparison with adult-onset schizophrenia.4,12

Distinguishing between adult-, childhood-, and early-onset schizophrenia is important, as childhood-onset schizophrenia is often characterized by a higher likelihood of speech, language, and/or educational disabilities and more severe intelligence deficits than early-onset schziophrenia.2–4 Driver and colleagues found that these symptoms are evident in 67% of patients with childhood-onset schizophrenia.2 In contrast, patients with early-onset schizophrenia tend to exhibit higher suicidality, more depressive symptoms, and a longer duration of untreated psychosis.11 Furthermore, patients with childhood-onset schizophrenia are more likely to have an attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder diagnosis, whereas patients with early-onset schizophrenia are more likely to have a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, substance use disorder, or an organic brain disorder.3 There are conflicting data regarding differences in onset between male and female patients in childhood- and early-onset schizophrenia, but it is thought that male patients with early-onset schizophrenia may be more vulnerable to neurodevelopmental comorbidities, and early illness onset has been linked with a higher genetic predisposition in female patients.3,4

Diagnosing childhood- and early-onset schizophrenia presents several challenges.4 Diagnoses are often delayed due to similarities with normal childhood fantasies, obsessive-compulsive disorder symptoms, autism spectrum disorders, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.4 Substance abuse in adolescents can further complicate diagnosis.4 Key risk factors for both childhood- and early-onset schizophrenia include an urban rearing environment, childhood trauma, migration and minority status, traumatic brain injury, and substance use.13 Clinical considerations that are important to note in childhood- and early-onset schizophrenia involve individualized antipsychotic dosing due to age-related differences in metabolism and side effects.4 Early-onset schizophrenia increases the risk of treatment-resistant schizophrenia (TRS), requiring expertise in diagnosing TRS and using clozapine.4 Psychosocial interventions are also important due to associated cognitive deficits and reduced quality of life.4

Hidden in the golden years: Uncovering schizophrenia’s late emergence

Although schizophrenia typically presents earlier in life, at least 20% of patients experience onset after the age of 40.6 Despite recommendations by Maglione and colleagues and Vahia and colleagues, based on data from several studies, late- and very late–onset schizophrenia-like psychosis are not included as subtypes in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition.6,14,15 The study of late-onset schizophrenia began with Manfred Bleuler, and it has since been noted that while late-onset schizophrenia and onset before the age of 40 share similar symptom profiles, there are significant differences.15 Patients with late-onset schizophrenia tend to exhibit lower severity of positive symptoms and less affective flattening.6,14,15 Cognitive impairment and cognitive deterioration are prevalent across all age groups, but impairments in executive functions are notably observed in those with late-onset schizophrenia.9,16 Additionally, Fagerlund and colleagues found that there are more prominent cognitive symptoms, such as more severe deficits in working memory and verbal memory, in patients with early- or late-onset schizophrenia compared with patients with adult-onset schizophrenia.4,12 Patients with late-onset schizophrenia are also more likely to experience visual, tactile, and olfactory hallucinations with running commentary.6 Patients with very late–onset schizophrenia-like psychosis, on the other hand, are less likely to experience negative symptoms and formal thought disorders compared with patients with late- or early-onset schizophrenia 15 but have a higher likelihood of impaired learning and retention.9

Diagnosing and treating late- and very late–onset schizophrenia-like psychosis involves specific clinical considerations.15 Late- and very late–onset schizophrenia-like psychosis are both more prevalent in female patients.9,15 Key risk factors to note in patients with late-onset schizophrenia include psychosocial factors proximal to psychosis onset, such as unemployment and migration, as well as physical health problems.13 For patients with late- and very late–onset schizophrenia, a combination of pharmacological and psychosocial/behavioral management approaches is recommended.15 It is also important to note that approximately 60% of very late–onset schizophrenia-like psychosis cases are secondary psychosis caused by neurodegenerative diseases such as dementia.9 Therefore, distinguishing secondary psychosis from very late–onset schizophrenia-like psychosis is crucial.9

Bridging generations: Navigating schizophrenia across age groups

While schizophrenia traditionally manifests during early adulthood, its occurrence in children or elderly individuals poses a significant diagnostic challenge, with no explicit framework from clinical guidelines on the topic.4,6 Identifying and accurately diagnosing schizophrenia in these patient populations is crucial yet complex due to overlapping symptoms with other developmental stages or age-related conditions.4,9 This highlights the pressing need for improved diagnostic tools, enhanced clinician awareness, and collaborative care to ensure timely intervention and appropriate management.4

Further reading

Immonen J, et al. Age at onset and the outcomes of schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Early Interv Psychiatry 2017;11:453–460.

A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effect of age at onset on the long-term clinical, social, and global outcomes of schizophrenia.Zhang Y, et al. Abnormal functional connectivity of the striatum in first-episode drug-naive early-onset schizophrenia. Brain Behav 2022;12:e2535.

The findings in this study highlight abnormal functional connectivity between the striatum and other brain regions in early stages of schizophrenia. This supports the idea that neurodevelopmental disruption plays a role in both cause and manifestation of schizophrenia.Vernal DL, et al. Long-term outcome of early-onset compared to adult-onset schizophrenia: A nationwide Danish register study. Schizophr Res 2020;220:123–129.

This study compared the outcomes of early- and adult-onset schizophrenia and suggests that patient characteristics other than age of onset may significantly affect outcomes

Cite this article as The age spectrum of schizophrenia: Early to late onset. Connecting Psychiatry. Published June 2025. Accessed [month day, year]. [URL]

-

World Health Organization. Schizophrenia. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/schizophrenia. Last accessed: September 2024.

-

Driver DI, et al. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 2013;22:539–555.

-

Jerrell JM & McIntyre RS. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2016; 18:10.

-

Correll CU, et al. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2024;82:57–71.

-

NIMH. Schizophrenia. Available at: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/schizophrenia. Last accessed: September 2024

-

Maglione JE, et al. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2014;27: 173–178.

-

Rapoport JL et al. Mol Psychiatry 2012;17:1228–1238.

-

Gogtay N, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008;105: 15979–15984.

-

Monji A & Mizoguchi Y. Neuropsychobiology 2022;81:98–103.

-

Clemmensen L, et al. BMC Psychiatry 2012;12:150.

-

Coulon N, et al. Brain Behav 2020;10:e01495.

-

Fagerlund B, et al. Psychol Med 2021;51:1570–1580.

-

Chen L, et al Compr Psychiatry 2018;155–162.

-

Vahia IV, et al. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2010;122:414–426.

-

Howard R, et al. Am J Psychiatry 2000;157:172–178.

-

Mosiolek A, et al. BMC Psychiatry 2016;16:37.

SC-US-77208

SC-CRP-17284

February 2025

Related content

Schizophrenia Primer 3 of 3: Cognitive Impairment Associated With Schizophrenia (CIAS)

Sign up now for new features

The newsletter feature is currently available only to users in the United States

*Required field