Early to Rise: Roles of Brain Structural and Neurochemical Imbalances in Cognitive Impairment Associated with Schizophrenia

In summary

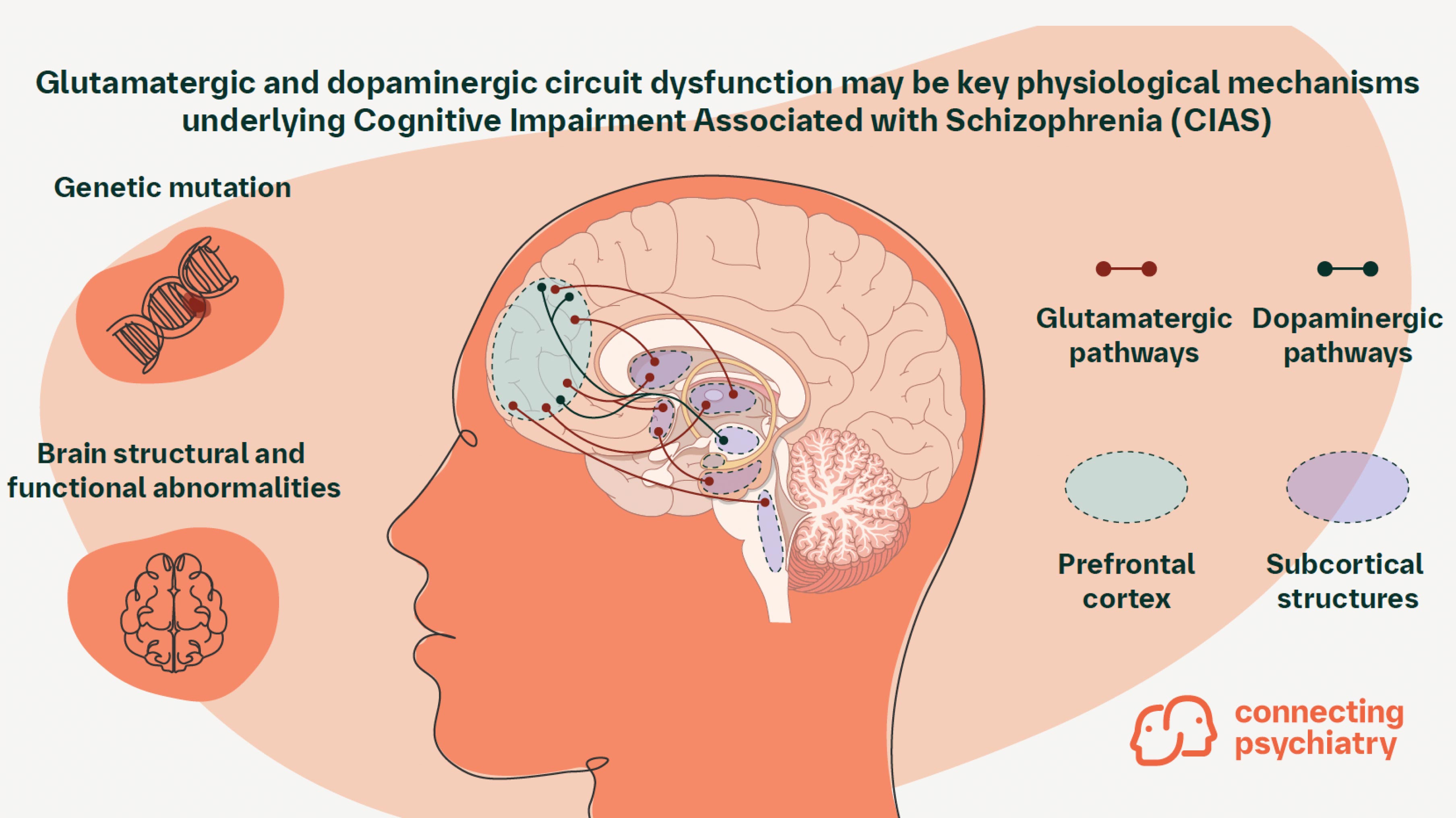

- Schizophrenia is a whole brain illness characterized by neurochemical deficits across multiple brain regions

- Cognitive impairment associated with schizophrenia (CIAS), a hallmark feature of the illness, may be detectable during early adolescence, and progressively worsens with age

- Abnormal development of more recently evolved, late-developing brain regions is thought to contribute to the onset of cognitive symptoms during adolescence

- Recent evidence indicates that glutamatergic and dopaminergic circuit dysfunction may be key physiological mechanisms underlying the onset of CIAS in adolescence

Introduction

Cognitive impairment associated with schizophrenia (CIAS) is thought to involve a combination of structural brain abnormalities and physiological changes during adolescence.1,2 The precise biological basis of CIAS is still being actively investigated, and some evidence suggests that late developing brain regions, such as those involved in cognitive processes, are preferentially affected.3,4 At the neurochemical level, recent genome-wide association studies (GWAS) revealed that dysfunction across multiple neurotransmitter systems, including glutamatergic and dopaminergic circuits, may play key roles in the onset of CIAS and warrant further exploration.1,4-7 Here we provide an overview of key changes in brain regions, structural abnormalities, and neurochemical mechanisms associated with the onset of CIAS.

Dysfunction in multiple brain regions underlies deficits in cognition

The development of the mature brain involves a complex interplay of structural and neurochemical events that occur during adolescence.8 Notably, subtle cognitive impairments may start to appear in early adolescence, prior to psychosis, and may be relatively stable once symptoms appear.1 Due to the timing of symptom onset, more recently evolved, late developing brain regions specific to humans are thought to be most affected.3,9 These include regions that regulate higher order cognitive functions, such as the prefrontal cortex (PFC).9 Though current research has focused on PFC dysfunction in CIAS, neuroimaging has shown that posterior parietal, auditory, and visual cortical abnormalities may also contribute to cognitive symptoms.10-12 Furthermore, additional alterations implicated in CIAS have been observed in other regions involved in normal cognition, such as the hippocampus, amygdala, and cerebellum.13 Cognitive deficits correlate to structural abnormalities in these regions, such as reductions in gray matter volume and white matter integrity.2 Together, these findings indicate that CIAS onset involves not just a single brain region, but multiple areas and neural networks.

Altered glutamatergic signaling is implicated in CIAS pathophysiology

Alterations in multiple neurochemical pathways have been proposed to contribute to CIAS onset. Several lines of evidence has suggested that one of these pathways, the glutamatergic neurotransmitter system, may contribute to cognitive impairments in schizophrenia.1 Genomic analyses from two studies of nearly 77,000 individuals with schizophrenia identified 120 commonly mutated genes across patients, many of which encode proteins with specific functions in glutamatergic signaling.5,6 N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors, the primary receptors for glutamate in the nervous system, emerged as a potential driver of schizophrenia symptom onset in adolescence.6 Mutations in the GRIN2A gene, which encodes GluN2A, a specific ligand-gated NMDA receptor subunit, have been repeatedly documented in individuals with schizophrenia and have also been associated with the early onset of schizophrenia symptoms in children.5,6,14,15 GRIN2A increases in expression levels throughout adolescence, correlating with the timing of schizophrenia symptom onset.6 These mutations are thought to reduce NMDA receptor and neural functioning and alter neural plasticity, which may contribute to cognitive impairment in individuals with schizophrenia.16 Other pathophysiological events that affect the glutamatergic pathways, such as excessive pruning of glutamatergic terminals during the second and third decades of life, have also been implicated in CIAS onset.1,17

Evidence of abnormal dopaminergic function in schizophrenia and cognitive impairment

Abnormalities in dopaminergic pathways have been hypothesized to contribute to schizophrenia symptom onset.1 To date, few genetic variants directly involved in dopaminergic signaling have been detected.18 Previous GWAS analyses revealed 108 commonly altered gene loci in patients with schizophrenia; of these loci, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the vicinity of the dopamine receptor D2 (DRD2) gene, have been detected.19 However, the relationship between these SNPs and the onset of schizophrenia symptoms has not been extensively evaluated.20 Additional gene variants that encode postsynaptic signaling proteins that act downstream of dopamine transmission (e.g. Akt serine/threonine kinase) have also been observed.20 Further, a genetic basis of dopaminergic signaling in CIAS remains elusive, indicating that external factors may be the primary driver of dopaminergic dysfunction in schizophrenia.4 Past imaging studies of patients with schizophrenia showed that abnormally increased dopaminergic activity in the striatum and other subcortical regions is correlated with positive symptoms of schizophrenia.1,21 Though no conclusive link between dopamine and impaired cognition in schizophrenia has been established, prevailing theories suggest that an imbalance in dopaminergic signaling, either hyper- or hypoactive neurotransmission, may alter the concentration of cortical dopamine and subsequently impair cognition.4

Conclusion

Several neurobiological changes may underpin the origins of CIAS including changes in brain architecture, alterations to grey and white matter structure, and dysfunction across key neural signaling pathways.1,2 There is still much that we do not fully understand about the timing of CIAS onset, including how alterations in specific brain regions and neurochemical systems give rise to cognitive deficits. Furthermore, investigation into how specific genetic variants and environmental factors are involved in CIAS pathophysiology may provide valuable candidates for future therapeutic exploration. Collectively, a more complete understanding of the pathophysiology of CIAS may help inform future treatment plans and improve the quality of care for individuals suffering from schizophrenia.

Further reading

Javitt DC, et al. Cognitive impairment associated with schizophrenia: from pathophysiology to treatment. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2023;63:119-141.

Review article discussing the roles of glutamatergic and dopaminergic theories of neurocognitive impairments in schizophrenia and novel, biomarker-driven, therapeutic advances in the fieldKarlsgodt KH, et al. Structural and functional brain abnormalities in schizophrenia. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2010;19:226-231.

Review article focusing on the MRI evidence for brain structural and connectivity abnormalities in patients with schizophrenia

-

Javitt DC. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2023;63:119-141.

-

Karlsgodt KH, Sun D, and Cannon TD. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2010;19:226-231.

-

Hill J, et al. PNAS. 2010;107:13135-13140.

-

McCutcheon RA, Krystal JH, and Howes OD. World Psychiatry. 2020;19:15-33.

-

Trubetskoy V, et al. Nature. 2022;604:502-508.

-

Singh T, et al. Nature. 2022;604:509-516.

-

D’Ambrosio E, et al. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2019;291:34-41.

-

Ciccia AH, et al. Top Lang Disord. 2009;29:249–265.

-

Selemon LD and Zecevic N. Transl Psychiatry. 2015;5:e623.

-

Yildiz M, Borgwardt SJ, Berger GE. Schizophr Res Treatment. 2011;2011:581686.

-

Javitt DC and Sweet RA.Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015;16(9):535-550.

-

Adámek P, Langová V, Horáček J. Schizophrenia. 2022;8:27.

-

Khalil M, et al. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2022;132:37-49

-

Hojlo MA, et al. Genes. 2023;14:779.

-

Shepard N, et al. Scientific Reports. 2024;14:2798.

-

Harrison PJ and Bannerman DM. Mol Psychiatry. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-023-02265-y.

-

Johnson MB and Hyman SE. Biol Psychiatry. 2022;92:440-442.

-

Kruse AO and Bustillo JR. Transl Psychiatry. 2022;12:500.

-

Ripke S, et al. Nature. 2014;511(7510):421.

-

Howes OD, et al. Biol Psychiatry. 2017;81:9-20.

-

Kegeles LS, et al. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:231-239.

Cite this article as Early to Rise: Roles of Brain Structural and Neurochemical Imbalances in Cognitive Impairment Associated with Schizophrenia. Connecting Psychiatry. Published April 2024. Accessed [month day, year]. [URL]

SC-US-76945

SC-CRP-16052

July 2024

Related content

More Than the Sum of Its Parts: The Etiology of Schizophrenia

Sign up now for new features

The newsletter feature is currently available only to users in the United States

*Required field