Article In Focus

Is fear overgeneralization specific to aversive stimuli in PTSD?

Elucidating behavioral and functional connectivity markers of aberrant threat discrimination in PTSD

– Keefe JR, et al. Depress Anxiety. 2022;39:891–9011

Natural environments are typically quite complex and dynamic. Through experience and exploration, discrete components of the environment, known as cues, become associated with events that are critical for survival. Cues have little hedonic value until they are paired with a salient outcome.2-4

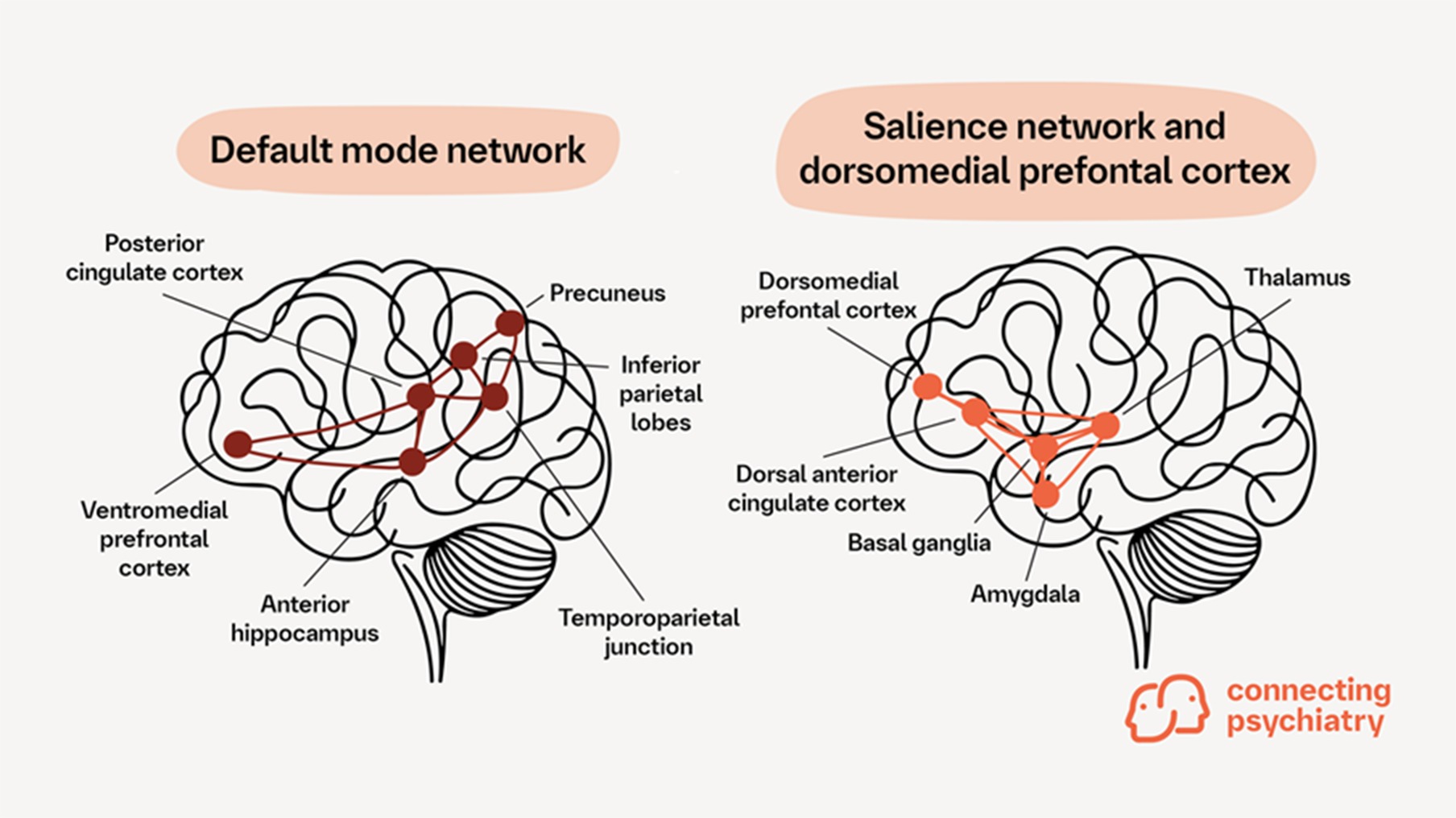

In life-threatening situations, threat detection increases the probability of survival due to the reaction to aversive cues that predict danger (avoidance or confrontation) versus when danger is already imminent.5 Discriminating threat levels is attributed to the complex interplay between two key brain networks: the default mode network (DMN) and the salience network.1

The DMN consists of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, posterior cingulate cortex, precuneus, inferior parietal lobes, temporoparietal junction, and anterior hippocampus.1,6 The salience network consists of the thalamus, dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, basal ganglia, and amygdala, and is closely associated with the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex1,7

Patients with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) exhibit impairments in cue discrimination and an exaggerated fear response to cues resembling the original predictive stimulus or to cues that are aversive but not predictive of danger.1,8 As a result, patients with PTSD tend to display fear-related responses towards both aversively reinforced conditioned stimuli and non-reinforced, neutral stimuli.1 It remains unclear whether threat overgeneralization is a result of a more general impairment in stimuli discrimination or a specific impairment related to aversive stimuli.1 Functional networks that mediate discrimination of threat cues versus neutral or aversive cues may be therapeutic targets for PTSD.1

Keefe and colleagues examined stimuli discrimination between participants with PTSD (n=33) and participants without PTSD (trauma-exposed [n=43] and healthy controls [n=32]) by assessing responses to emotionally neutral and emotionally aversive stimuli.1

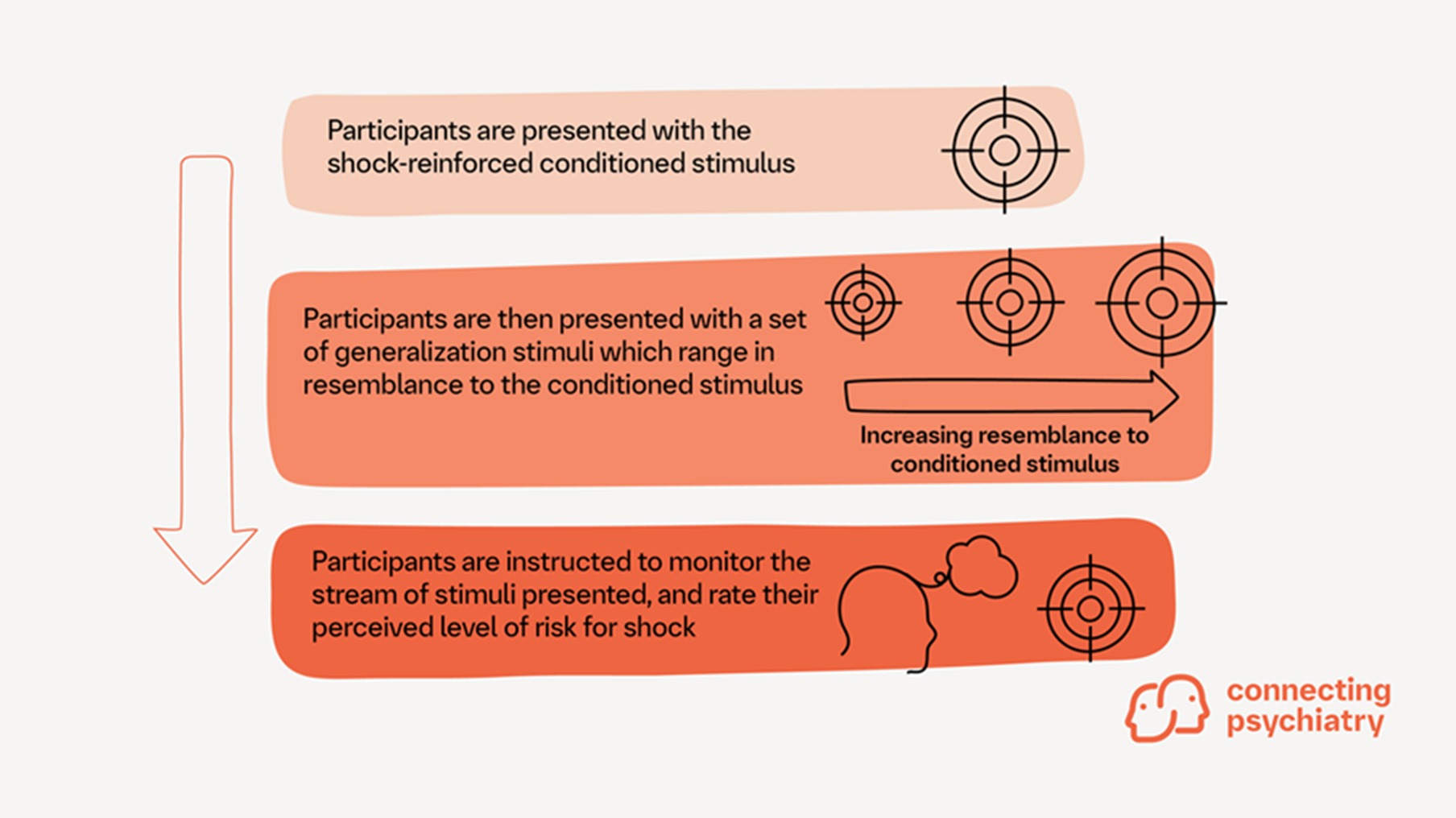

Emotionally neutral discrimination was assessed using the Modified Benton Task. Emotionally aversive discrimination was assessed with a threat discrimination task. During this task, participants were presented with a conditioned shock-induced stimulus and were then instructed to monitor a series of stimuli and rate their perceived level of risk for shock as quickly as possible, as illustrated in the figure below.1

Functional connectivity patterns in the brain were also assessed to identify brain networks associated with task performance.5

PATIENTS WITH PTSD WERE LESS ABLE TO DISCRIMINATE BETWEEN SIMILAR VISUAL STIMULI THAN PATIENTS WITHOUT PTSD

Participants with PTSD did not differ in performance on the emotionally neutral discrimination task when compared with participants without PTSD.1

During the emotionally aversive discrimination task, participants with PTSD were less able to discriminate between similar visual stimuli than those without PTSD.1 Participants with PTSD displayed linear increases in risk ratings as the stimulus increased in resemblance to the conditioned stimuli.1 In contrast, participants without PTSD provided higher risk ratings than those with PTSD for stimuli that more closely resembled the conditioned stimuli.1 These findings indicate that patients with PTSD can perform well on emotionally neutral discrimination tasks; however, discrimination between visual stimuli during emotionally aversive discrimination tasks is challenging.1 These challenges may be an underlying factor in the overgeneralization of threat in patients with PTSD.1

WHAT ARE THE KEY BRAIN REGIONS INVOLVED IN THREAT DISCRIMINATION?

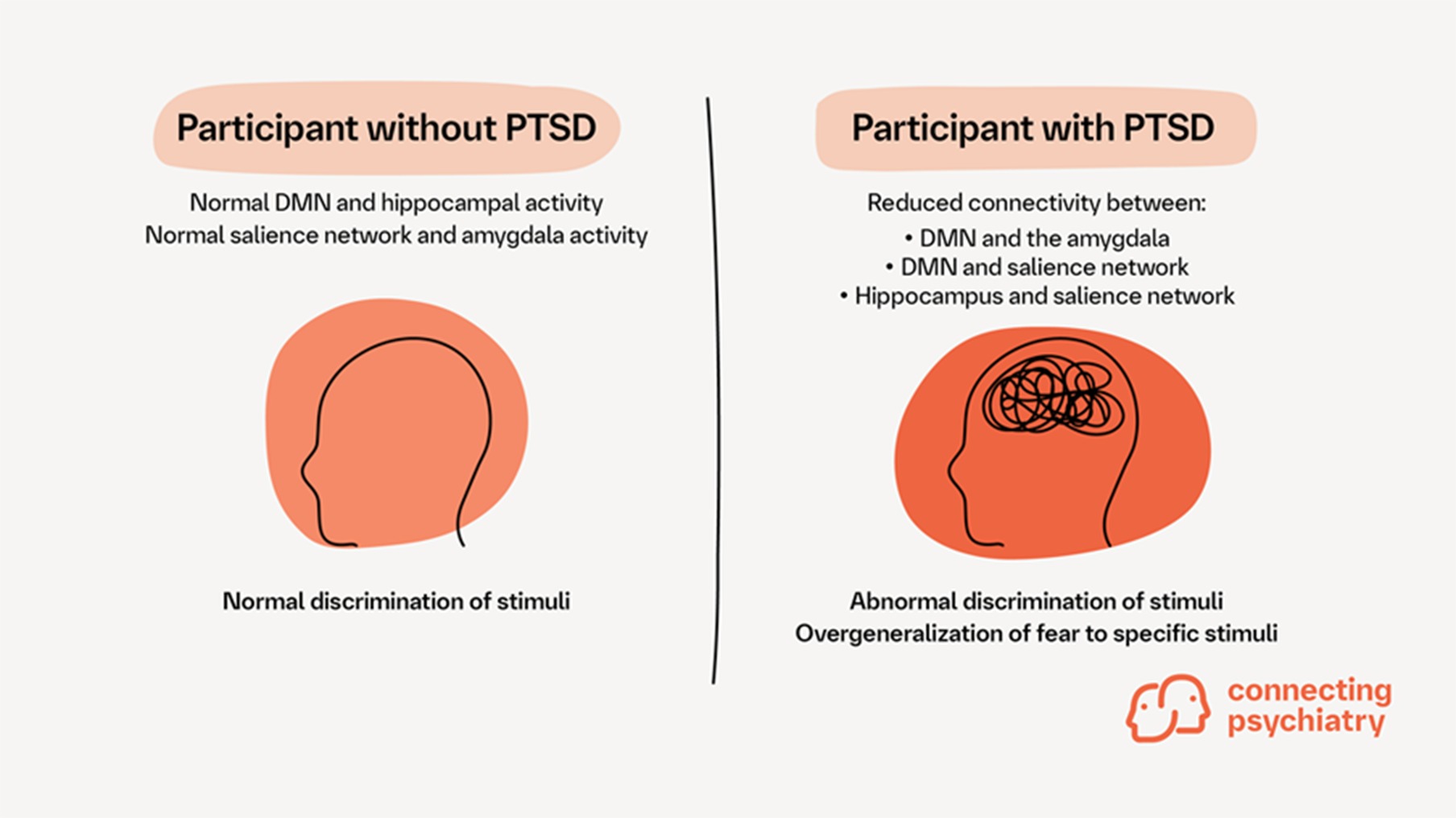

In participants with PTSD, reduced connectivity between the DMN and the amygdala, between the DMN and the salience network, and between the hippocampus and the salience network predicted higher risk ratings during the emotionally aversive discrimination task as the resemblance of stimuli to the conditioned stimulus increased.1 Participants without PTSD did not show this relationship.1 These findings suggest that the emotionally aversive discrimination system may be compromised in people with PTSD, leading to overly sensitive and non-specific processing.1

In contrast, increased connectivity of the DMN with the amygdala and the salience network may be associated with increased accuracy in the emotionally aversive discrimination task. This highlights the DMN’s potential role in applying environment and/or personal context to form emotional experiences, incorporating signals (such as fear) from the amygdala and the salience network.1

Impairments in emotionally aversive—but not emotionally neutral—discrimination may be threat specific in PTSD1

Dysregulated discrimination patterns may relate to a lack of input from regulatory brain areas (e.g., DMN/hippocampus) to threat-related brain areas (e.g., salience network/amygdala)1

Strong connectivity between the brain nuclei that support assigning threat to stimuli and discriminating between similar stimuli may protect against overgeneralization of fear and attribution of danger to neutral stimuli1

Therapeutic approaches that enhance the ability to discriminate between aversive and neutral cues may result in increased resting state functional connectivity within the DMN and salience network1

Investigating the covariance and temporality of changes in PTSD symptoms, emotionally aversive discrimination performance and network resting state functional connectivity during clinical trials can provide deeper insights into the mechanisms of effective PTSD treatment1

This approach may help identify which patients are most likely to benefit from specific interventions that modulate these neural networks, leading to more tailored and effective PTSD treatment1

Cite this article as Article in focus. Connecting psychiatry. Published May 2025. Accessed [month day, year]. [URL]

Abbreviations:

DMN, default mode network; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

-

Keefe JR, et al. Depress Anxiety 2022;39:891–901.

-

Silverstein SE, et al. Nature 2024;626:1066–1072.

-

Sih A, et al. Evol Appl 2011;4:367–387.

-

Shiner T, et al. Cereb Cortex 2015;25:3629–3639.

-

Adenauer H, et al. Biol Psychiatry 2010;68:451–458.

-

Heinonen J, et al. PLoS One 2016;11:e0162234.

-

Galandra C, et al. Sci Rep 2018;8:14481.

-

Fenster RJ, et al. Nat Rev Neurosci 2018;19:535–551.

SC-US-77987

SC-CRP-17083

February 2025

Related content

Guideline Digest: Post-traumatic Stress Disorder

Sign up now for new features

The newsletter feature is currently available only to users in the United States

*Required field