Factor It In: Poor Sleep Quality Can Be a Nightmare for Mental Health

The Factor It In series will illuminate the influences on mental health that arguably deserve greater attention. You will be provided with fresh perspectives through a discussion of the factors that impact the development of serious mental health conditions and a review of the literature on impact on disease course; ultimately, you may use this knowledge to inform discussions with your patient.

In summary

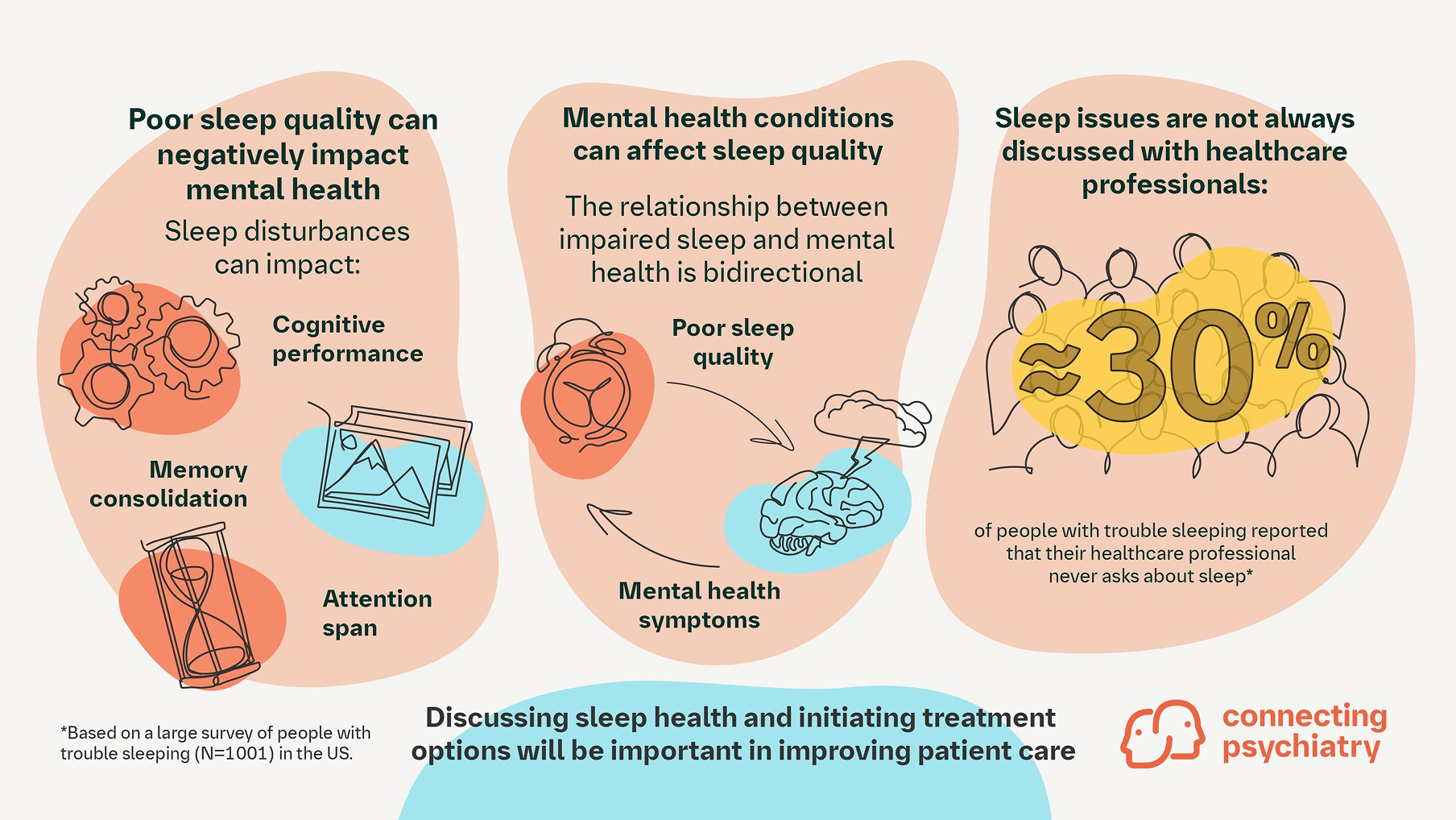

- Poor sleep is a consistent indicator and potential cause of poor outcomes across various mental health conditions

- Pre-existing mental health conditions can be precursors to sleep disorders, which can negatively impact condition progression

- Engaging patients in discussions about sleep concerns as part of routine care could enhance sleep quality and improve outcomes

The relationship between insufficient sleep and mental health conditions

Impaired sleep has been identified as potentially contributing to the incidence of mental health conditions.1 Research has shown that individuals who consistently experience poor quality or insufficient sleep are at an increased risk of experiencing frequent mental distress and developing mental health conditions such as anxiety, depression, or bipolar disorder.7,8 Sleep disturbances can also exacerbate existing mental health conditions and make them more difficult to manage.8,9 Individuals with comorbid insomnia and depression, for example, tend to have more severe depressive symptoms, longer treatment durations, and worse rates of remission than individuals with depression without sleep disturbance.10 Additionally, disturbed sleep has been shown to be a predictive factor in determining the occurrence and outcome of depression.10

There are several mechanisms through which impaired sleep may impact mental health. Firstly, inadequate sleep impairs cognitive performance, memory consolidation, and attention span.2–4 Additionally, the lack of sleep can disrupt mood and emotional regulation and increase thoughts of self-harm.4 Non-rapid eye movement (NREM) accounts for 80% of total sleep time and is primarily responsible for cerebral restoration and recovery, memory consolidation, and hormone level modulation.11 Disrupted NREM cycles are associated with increased severity of mental health conditions and suicidal ideation due to reduced consolidation of positive emotional content.11

Mental health conditions may affect sleep quality

The relationship between impaired sleep and mental health is bidirectional. Mental health conditions can contribute to disrupted sleep patterns, creating a vicious cycle in which poor sleep worsens mental health symptoms, which in turn further disrupts sleep.4,5 People living with mental health conditions, such as depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, and anxiety, are more prone to experience sleep disorders, including obstructive sleep apnea and insomnia; these disorders can have further detrimental effects on mental health.7,8

One of the most common and distressing symptoms experienced by individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is nightmares.12 Disrupted sleep and trauma-related nightmares, according to some researchers, may potentially have a role in the development of PTSD and exacerbate PTSD symptom severity, distress, and associated functional impairment.12

Recognizing the importance of addressing impaired sleep in relation to mental health is crucial for effective prevention and treatment strategies. Despite this, in a large US survey, approximately 30% of people with trouble sleeping reported that their healthcare professionals do not ask them about sleep issues.6 Thus, inquiring about sleep problems might help address a common, underappreciated concern.

How can healthcare professionals help?

Assessing and treating any underlying sleep issues in patients with mental health concerns is a key factor in establishing effective diagnosis and treatment.13 Engaging patients with empathy and having discussions to better understand sleeping patterns could potentially help identify underlying problems. There are several treatments and activities that are available that can be offered to patients depending on their individual needs; these may include pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions and lifestyle modification advice.13-17

Pharmacological interventions involve treatment with various sleep medications available as prescription drugs and over-the-counter products.17 Non-pharmacological interventions include promoting healthy sleeping habits through patient education on good sleep hygiene practices. These habits include establishing regular bedtime routines, creating a comfortable sleeping environment, limiting exposure to electronic devices before bed, and avoiding caffeine and alcohol.13 Mindfulness meditation, physical activity, and exercise are also key methods that can be employed for improving sleep quality.14,15 Lifestyle modification advice includes practical tips to empower patients, such as how to turn healthy behaviors into habits (i.e., repeating a desired behavior in the same environment until it becomes automatic and effortless).16

Other non-pharmacological interventions include cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I), which is supported by a large body of evidence for the treatment of insomnia.13 CBT-I is recommended as the first-line treatment for chronic insomnia by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and American College of Physicians.13 Practitioners can also refer patients to sleep specialists depending on the severity of the patients’ needs.18

Good sleep is important for overall health and functioning; understanding sleeping problems can provide valuable information about a patient's overall health and inform care. Routinely inquiring and counseling patients about lifestyle factors that may impact sleep can be useful in overall patient care and treatment.13 By understanding the link between impaired sleep and mental health conditions, we can take proactive steps toward promoting better overall well-being and reducing the incidence of these debilitating mental health conditions.

Further reading

- Ramar K, et al. Sleep is essential to health: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine position statement. J Clin Sleep Med 2021;17:2115–2119.

Expert consensus describing the importance of sleep and suggested strategies to promote healthy sleep as a public health focus - Freeman D, et al. The effects of improving sleep on mental health (OASIS): a randomised controlled trial with mediation analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2017;4:749–758.

A randomized controlled trial following 3755 participants that provides evidence that insomnia is a causal factor in the occurrence of psychotic experiences and other mental health problems - Deschênes S, et al. Depressive symptoms and sleep problems as risk factors for heart disease: a prospective community study. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 2019;29:e50.

A study looking into the associations between depressive symptoms, sleep problems, and the risk of developing heart disease in a Canadian community sample. The study confirmed that depression and diagnosed sleep disorders or long sleep duration are independent risk factors for heart disease and associated with a stronger risk of heart disease when occurring together - Scott AJ, et al. Improving sleep quality leads to better mental health: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Sleep Med Rev 2021;60:101556.

A meta-analysis and review of randomized controlled trials that assesses the effects of an intervention that improved sleep on composite mental health, as well as on specific mental health difficulties (depression, anxiety, stress, psychosis spectrum experiences, suicidal ideation, PTSD, rumination, and burnout)

Cite this article as Factor It In: Poor Sleep Quality Can Be a Nightmare for Mental Health. Connecting Psychiatry. Published May 2024. Accessed [month day, year]. [URL]

-

Freeman D, et al. Lancet Psychiatry 2017;4:749–758.

-

Bubu OM, et al. Sleep 2017;1:40.

-

Ma Y, et al. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e2013573.

-

Kansagra S. Pediatrics 2020;145:S204–S209.

-

Benca RM. J Clin Med 2023;12:2498.

-

Blackwelder A, et al. Prev Chronic Dis 2021;18:E61.

-

Drakatos P, et al. Sci Rep 2023;13:8785.

-

Kallestad H, et al. BMC Psychiatry 2012;12:179.

-

Fang H, et al. J Cell Mol Med 2019;23:2324–2332.

-

Steffey MA, et al. Can Vet J 2023;64:579–587.

-

Merrill RM. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022;19:7957.

-

Phelps AJ, et al. Sleep 2018;1:41.

-

Sun J, et al. J Clin Sleep Med 2021;17:1083–1091.

-

Lederman O, et al. J Psychiatr Res 2019;109:96–106.

-

Peters AL, et al. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2022;24:645–660

-

Gardner B, et al. Br J Gen Pract 2021;62:664–666.

-

Chun W, et al. Medicine (Baltimore) 2021;100:e26678.

-

Chaput JP, et al. Prev Med Rep 2019;14:100851.

SC-CRP-14894

SC-US-76834

May 2024

Related content

Guideline Digest: Post-traumatic Stress Disorder

Sign up now for new features

The newsletter feature is currently available only to users in the United States

*Required field