Factor It In: Nurturing Mental Well-Being With Blue and Green Spaces

The Factor It In series will illuminate the influences on mental health that arguably deserve greater attention. You will be provided with fresh perspectives through a discussion of the factors that impact the development of serious mental health conditions and a review of the literature on impact on disease course; ultimately, you may use this knowledge to inform discussions with your patient.

In summary

- Urbanization trends threaten our connection with nature, posing risks to the mental well-being of those living in urban areas

- Nature-based interventions show promise in enhancing cognitive function, reducing symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and improving overall mental health

- Governments and organizations worldwide are recognizing the pivotal role of green and blue spaces in mental well-being and are advocating for accessible nature spaces in urban areas

In today's rapidly urbanizing world, our connection with nature is diminishing. Currently, over 55% of the world’s population lives in urban areas, a figure expected to rise to 68% by 2050.1 Various factors, including limited access to nature in urban areas, safety concerns, increased indoor and screen time, and various psychological barriers, have contributed to our dwindling contact with nature.2,3 Urban living correlates with higher risks of mental health conditions such as anxiety, depression, and schizophrenia, with these conditions being approximately 56% more common in urban areas than in rural areas.4–6 In this article, we explore literature on the relationship between nature and mental health, including the significance of blue and green spaces, while highlighting the importance of reintegrating natural elements into urban environments.

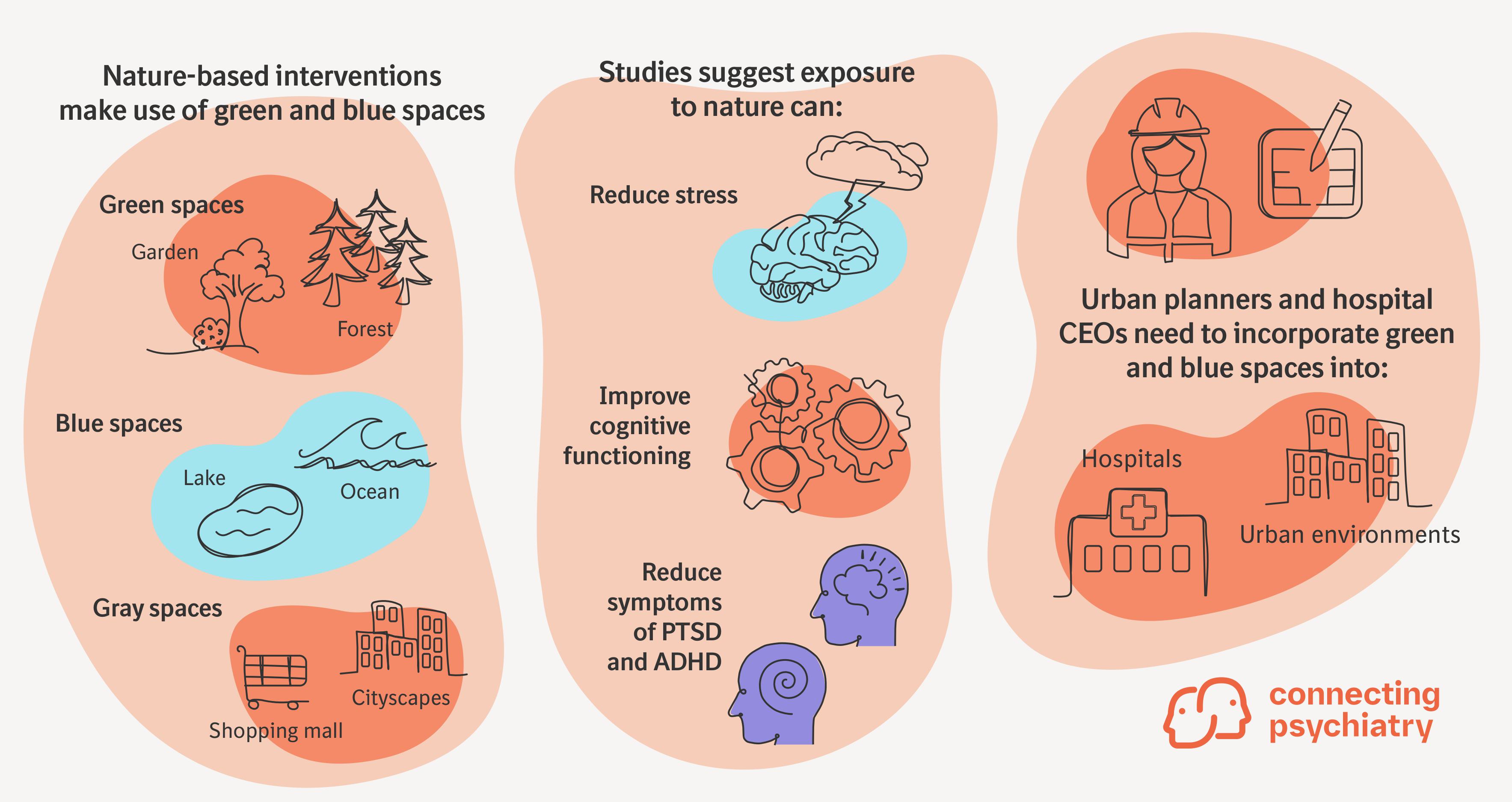

Nature’s palette: Exploring the spectrum of natural spaces

Several research articles describe nature in the context of mental health as green and blue spaces.3,4,7–9 Green spaces encompass urban parks, natural environments, urban forests, and gardens.3,7 Blue spaces include rivers, fountains and sea walls, coastal areas, lochs, wetlands, the ocean, and beaches.3,7 In contrast, gray spaces refer to the urban built environment, such as cityscapes, sidewalks, shopping malls, and other urban landscapes.7 Nature-based interventions make use of these natural green and blue environments by integrating activities such as hiking or fishing to cultivate connections with nature.3,7

Nature’s healing touch: Potential impact of nature on mental health

Connecting with nature in blue and green spaces is widely perceived to alleviate stress and anxiety.7,10–12 A survey of 994 US youths found that 51.6% of participants reported feeling calm when in nature, while 22.1% noted that it reduced their anxiety. However, 7.0% mentioned that being in nature sometimes made them feel isolated.10 Supporting these perceptions, a large-scale survey of 16,306 participants conducted across 18 countries found that a strong sense of connectedness to nature was linked to positive well-being and lower levels of mental distress. Frequent visits to green spaces were also associated with a reduced likelihood of using medication for depression.9

Real-world evidence further supports these perceived benefits, showing that contact with nature can potentially lead to stress reduction and improve working memory and cognitive functioning.4,13,14 For instance, a study in 63 participants using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) examined the effects of exposure to urban versus natural environments on stress-related brain regions. The study found a decrease in amygdala activation when participants took a 1-hour walk in a forest compared with an urban busy street.4 In another study with 30 participants, those exposed to nature in an indoor site (some vegetation) and a semi-indoor site (a large amount of vegetation and view of the sky) for 5 minutes exhibited higher working memory performance in a cognitive task compared with participants exposed to the baseline site (no vegetation).13 A further study involving 25 healthy individuals showed higher connectivity (assessed using fMRI) in brain regions associated with attention, the default mode, and somatomotor networks when participants viewed photographs of natural environments versus built environments.14

Nature-based interventions have also shown promising effects in reducing symptoms of mental health conditions such as PTSD and ADHD.15,16 Time spent in nature correlated with decreased symptoms of PTSD in 49 veterans when used as an adjunct to cognitive processing therapy.15 Furthermore, a nationwide study in the US found that outdoor activities in green spaces were more effective in reducing symptoms of ADHD in children compared with activities in other settings.16

Understanding our bond: The hypotheses behind our connection to nature

The impact of nature on mental health is often explained through the “biophilia hypothesis,” which suggests that humans have an innate affinity for nature due to our evolutionary history.17 Based on this hypothesis, two major theories exist on why nature might affect mental well-being. The Attention Restoration Theory hypothesizes that the mental fatigue associated with modern life is associated with a depleted capacity to direct attention. Spending time in natural environments enables people to overcome this mental fatigue and restore the capacity to direct attention.13–15,17 The Stress Reduction Theory hypothesizes that spending time in nature might influence feelings or emotions by activating the parasympathetic nervous system to reduce stress and autonomic arousal because of people’s innate connection to the natural world.14,15,17

Navigating nature: Bridging the research gap

While nature-based interventions show promising benefits, current research has important limitations and considerations. It is often unclear whether the positive effects are due to the outdoor settings themselves or the activities performed there.8,15 Additionally, most studies are conducted in high-income, urbanized countries, which may not represent global populations.7,9 Furthermore, there is no standardized method for measuring time spent in nature or for defining nature contact, which may lead to inconsistencies in research findings.11 Addressing these gaps is crucial for fully understanding and harnessing the potential of nature-based interventions for mental health conditions.

Empowering nature-based solutions: Strategies and considerations

Organizations and governments worldwide recognize the importance of access to green and blue spaces for mental health and well-being. Below are some examples of key initiatives and recommendations:

The World Health Organization emphasizes that urban green spaces are essential for creating healthy, sustainable, and livable conditions12,18

The European Environment Agency advocates that people should have access to green space within a 15-minute walk from their homes12

The UK government is developing a 25-year plan to increase the connection between people and nature12

Since 1982, the Japanese Government has recommended the concept of “Shinrin yoku” or “forest bathing” and invested 4 million dollars between 2004 and 2012 to develop “Shinrin yoku” as a national health program to urge citizens to make use of the country’s woodlands19,20

Therapeutic hospital gardens (THGs) are increasingly being included in hospital developments21

THGs can be found in several hospitals worldwide:

Australia: Bendigo Hospital, Victoria and Queensland Children’s Hospital

Singapore: Khoo Teck Puat Hospital

US: Legacy Hospitals

Blending blue and green: Urban planning for mental well-being

As we continue to urbanize and densify our cities, it is essential that urban planners recognize the importance of incorporating green spaces in urban planning to mitigate the negative effects of urbanization on mental health.4,21,22 Mental health professionals might also have a crucial role to play in encouraging their patients to spend time outdoors in nature and engage in activities that promote physical activity and overall well-being.

If you want to read more articles, visit the In the Clinic section to stay up-to-date on the latest mental health insights.

Further reading

- Geneshka M, et al. Relationship between green and blue spaces with mental and physical health: a systematic review of longitudinal observational studies. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18:9010.

An article examining the associations between green and blue spaces with long-term mental and physical health conditions. - Astell-Burt T, et al. Green space and loneliness: a systematic review with theoretical and methodological guidance for future research. Sci Total Environ 2022; 847:157521.

A review on the health impacts of loneliness and how increasing green spaces in urban environments may help to reduce these health impacts.

Cite this article as Factor It In: Nurturing Mental Wellbeing with Blue and Green Spaces. Connecting Psychiatry. Published February 2025. Accessed [month day, year]. [URL]

-

World Health Organization. Urban Health. 2021. Available at: https://www.who.int/health-topics/urban-health/#tab=tab_1. Last accessed: April 2024.

-

Bratman GN, et al. Sci Adv 2019;5:eaax0903.

-

McCartan C, et al. Health Expect 2023;26:1679–1691.

-

Sudimac S, et al. Mol Psychiatry 2022;27:4446–4452.

-

Gruebner O, et al. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2017;114:121–127.

-

Davis J, et al. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2016;65:185–194.

-

Nejade RM, et al. J Glob Health 2022;12:04099.

-

White MP, et al. Sci Rep 2019;9:7730.

-

White MP, et al. Sci Rep 2021;11:8903.

-

Zamora AN, et al. BMC Public Health 2021;21:1586.

-

Holland I, et al. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18:4092.

-

McEwan K, et al. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16:3373.

-

Rhee JH, et al. Sci Rep 2023;13:13199.

-

Kühn S, et al. Sci Rep 2021;11:4110.

-

Bettmann JE, et al. J Clin Psychol 2021;77:2041–2056.

-

Kuo FE & Taylor AF. Am J Public Health 2004;94:1580–1586.

-

Jimenez MP, et al. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18:4790.

-

Bentley PR, et al. Ambio 2023;52:1–14.

-

Dose of Nature. Around the World. 2020. Available at: https://www.doseofnature.org.uk/around-the-world1. Last accessed: May 2024.

-

Song C, et al. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2016;13:781.

-

Nieberler-Walker K, et al. HERD 2023;16:260–295.

-

Kabish N, et al. Ambio 2022;51:1388–1401.

SC-US-77207

SC-CRP-16805

November 2024

Related content

Factor It In: Food For Thought

Sign up now for new features

The newsletter feature is currently available only to users in the United States

*Required field